Eco-Friendly or Eco-Shady?

Carbon Credits: More Than Meets The Eye

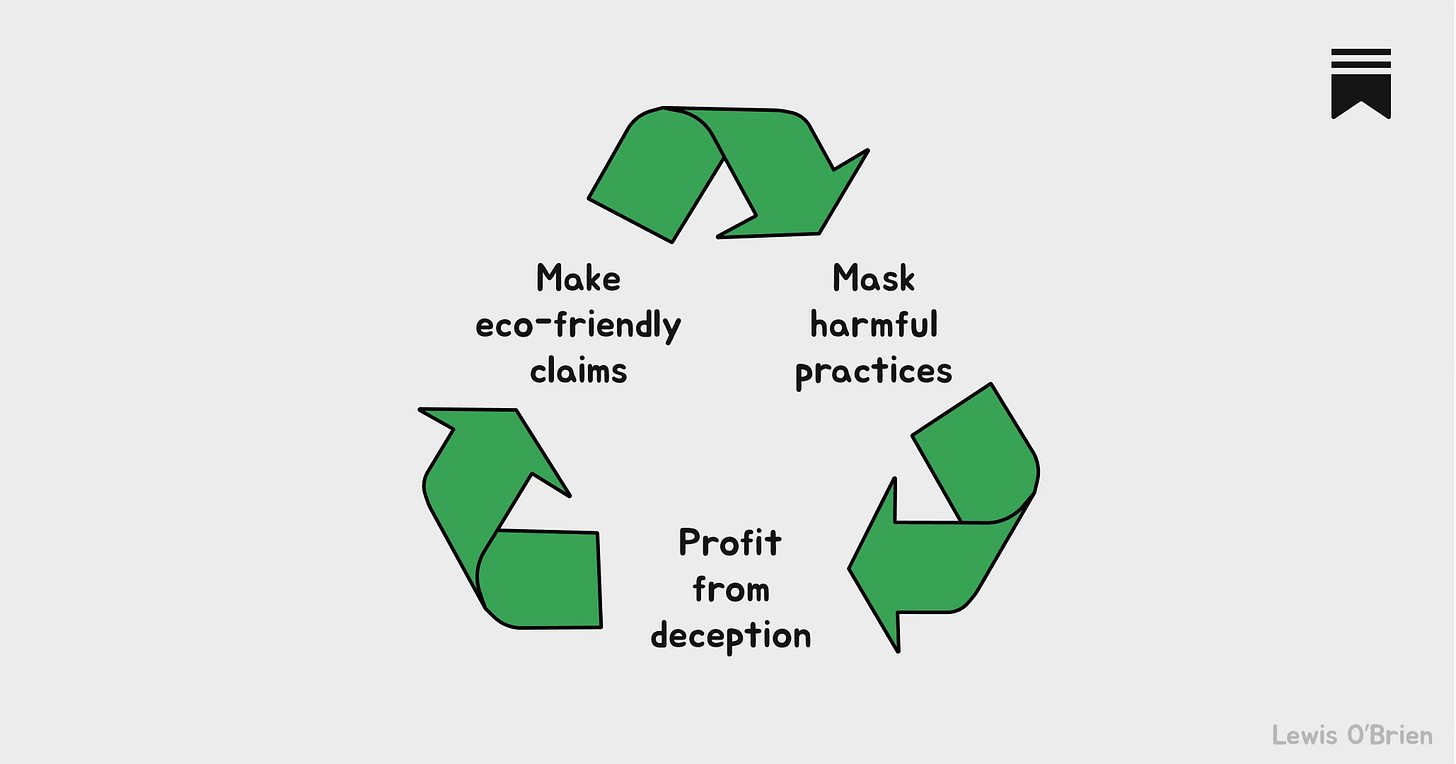

Greenwashing:

Activities by a company or an organisation that are intended to make people think that it is concerned about the environment, even if its real business actually harms the environment.

The term ‘greenwashing’ was coined back in 1986 when the environmentalist Jay Westerveld visited Fiji and noticed that the hotel asked guests to reuse their towels in order to “save the environment.”

A ploy to reduce laundry costs that distracts attention from the other ways that the hotel affects the environment.

Carbon credits are also frequently accused of greenwashing.

In principle, they are a good idea.

At their heart the logic is sound - one tonne of greenhouse gas emissions has the same impact on the climate irrespective of where it comes from.

Cutting emissions from a factory can be costly. If the owner could pay someone else to avoid the emissions, and at a fraction of the cost, then everyone is better off.

In practice, it’s much more challenging.

There are several risk factors that determine whether a credit will deliver on its claims.

They include:

Additionality — the reduction would have happened anyway

Over-crediting — more credits are issued than warranted

Non-permanence — carbon avoided or removed is only temporary

Indeed, a recent meta study evaluating the performance of 20% of all credits issued, found that less than 16% constituted real emission reductions.

Up until two decades ago the ‘Bubble’ in Nike Air trainers were filled with sulfur hexafluoride, a greenhouse gas 24,000 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

In 1997 Nike announced that it would phase it out ahead of future regulations.

That should have been the end of it — the project failed the additionality test. Instead, Nike sold the emission reduction as a carbon project, issuing credits that enabled other companies to carry on emitting.

A recent study examined the top 20 most active corporations in the carbon credit market during 2020-2023. All but one had pledged net-zero targets or claimed to provide carbon-neutral services. The report found that 87% of the credits used to help meet these commitments were low cost and at high risk of failing to deliver.

The use of low-quality credits undermines those who have invested in cutting their emissions, but it also has a more serious side-effect. It hinders the ability to channel capital to those natural ecosystems most vulnerable to exploitation and releasing carbon.

The lessen here is to always look for the hidden motive.

We often see bold statements from large organisations and take them at face value because we assume they’re too ‘big’ to get away with deception — but all it takes is a peek behind the curtain to see that shady practices go all the way to the top.

Look beyond anyone’s claims and you’ll usually find another motive.

Often that motive is harmless and aligns well with what they say, but sometimes it flies in the face of the message they are projecting.

This article was written in collaboration with Peter Sainsbury, an economist with over 25 years’ experience in energy and commodity markets.

His newsletter, Carbon Risk, is a great place to learn more!

Thanks for reading. We’re keen to hear your thoughts on this.

Join the conversation using the buttons below and we’ll try and get back to you as soon as possible.

Don’t forget to subscribe and share this article with your friends / colleagues.